Key Shots

It is also important to be aware of the camera’s relationship to the audience. For the most part the camera acts as our invisible third party representative in the scene, but this is not always the case. These are the key shots that serve a distinct narrative function within the scene:

- Establishing Shot – this is usually a wide shot that shows the setting and provides a environmental and sociological context for the action which is to follow.

- Master Shot – a camera shooting as an invisible observer is used to establish the geometry of the dramatic space and provide an illusion of objectivity

- Two Shot – a shot that shows two people in the frame and helps establish the changing relationship between them

- Shot and Reverse – a shot sequence most commonly used to film dialogue sequences (though it is important to distinguish the reverse from a reaction shot, they are not the same)

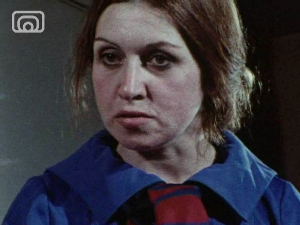

- Reaction Shot – this type of shot underscores key moments within the scene. At their most extreme, reaction shots can function as an exclamation mark; however, for the most part they enable the audience to work out what the character is thinking. This is very important since in a film we do not have easy access to a person's thoughts (as we do in a novel). Some films resort to narration; however, this changes the nature of the narrative, and is not always appropriate to the subject matter and themes of the film.

- Point of View (POV) Shot – here the camera appears to look through the eyes of a key character to show what they want or what they fear. Where the POV shot forms part of a longer 'POV sequence' it is used to establish the main desire or fear lines in the film that are critical to the audience's understanding of the narrative. For instance when you see one person looking longingly at another and cut back and forth from their POV shot to their different reactions shots (facial responses and body language), you know it can only mean one thing - they are really interested.

- Over the Shoulder Shot – this type of shot establishes an empathy with whoever's shoulder it may be (unless of course the camera is 'creeping up' on the character, see 'watcher shot') as well as establishing the distance between the character and what he or she is observing

- Cut-ins – these are shots that release key information necessary to understand the narrative, e.g. the time of day or a message scribbled on a note

- Watcher Shot – a staple of horror film where the camera moves against a fixed foreground to signify that the action is being observed by an as yet unknown observer (often accompanied by a corresponding change in the soundscape or music)

- Crossing the Line – here a clip is deliberately shot from an unfamiliar position (not established dramatically through the eyelines between the characters) to unsettle the audience. NB. It is also the most common 'mistake' made by professional filmmakers. The most common mistake of inexperienced filmmakers is not using a tripod.

- Breaking the Fourth Wall – this is where a character in the film directly addresses the audience or hams to the camera and breaks the illusion that the film is ‘real’.

All of these special shots may be underlined through the use, exaggeration or reduction of certain sounds.